Making sense of the statutory residence test (“SRT”)

A person’s residence status – for the purposes of this article whether they are resident for tax purposes in the UK – is incredibly important.

It determines what taxes are payable and the quantum of such payments.

With this in mind, one might be slightly surprised that it took until the 6 April 2013 for the legislators to enshrine a statutory test of residence.

Prior to this, it was generally the piecemeal body of case law which determined someone’s status along with HMRC’s long standing

guidance set out in IR20.

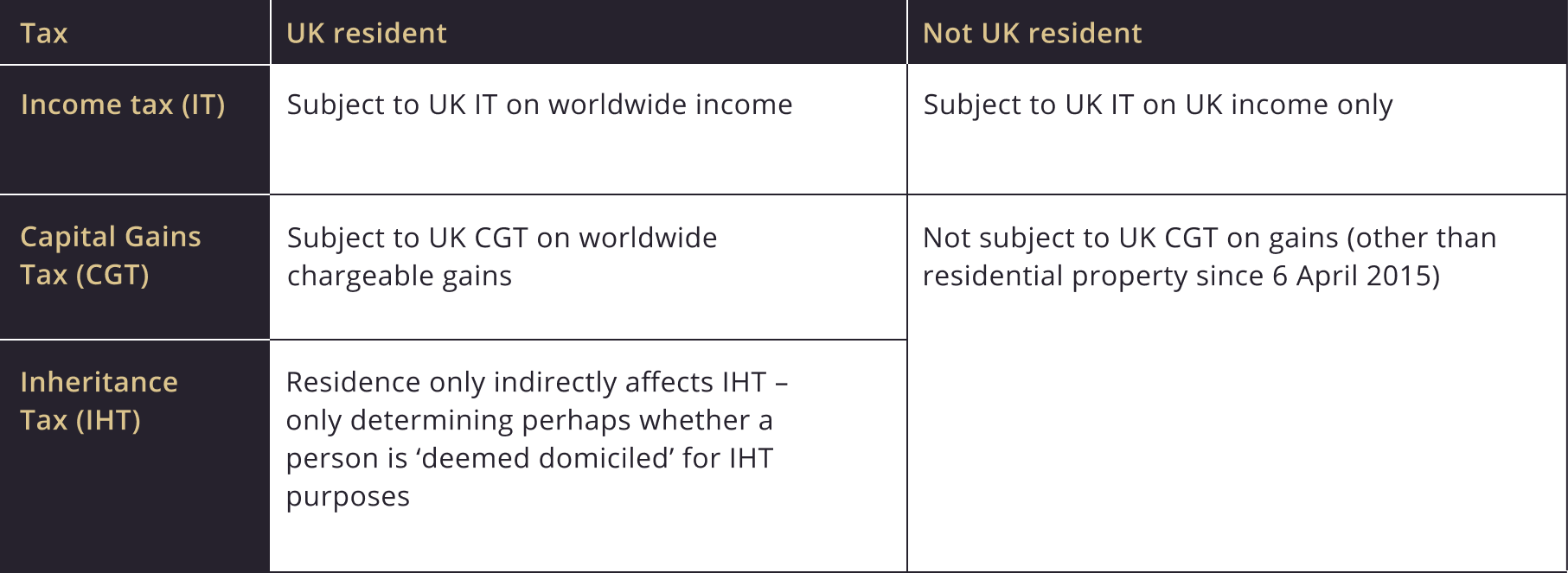

Residence status – liability to taxes

But, why does it matter?

Residence is the main determining factor for exposure to income taxes and capital gains tax.

Up to now, IHT is primarily concerned with one’s domicile position. However, as part of the surprising announcement in Spring Budget 2024 that significance of domicile will be removed from UK tax code, IHT will, in the future, be determined by residence.

An overview of the SRT

he SRT created a lot of criticism when introduced.

The rules can be quite complex. However, modern life can very complex. So, we shouldn’t be too surprised.

This contrasts with the case law (on which cases were being previously being determined) was decades, and in some cases centuries, old. Where, under this old case law international business involved time consuming and expensive journeys overseas, it is now exceedingly easy to travel to far flung countries.

What the SRT aims to do is set out are a number of objective tests. Even where the application of these test can be quite complex, If one, based on the facts, can fall the ‘right side of the line’ then one can plan with certainty that one is non-UK resident.

Where one can obtain certainty, then this must be an improvement on the old state of affairs.

The ‘SRT Roadmap’

General

he SRT can be thought of as a road map. However, it is a roadmap to a destination that nobody know at the outset.

The first stage is to determine whether one satisfies the ‘Automatic Overseas’ tests (“AO Tests”). If one does qualify as being ‘automatically overseas’ then, unsurprisingly, one is non-UK resident. One can consider the SRT journey over at this point.

If one does not meet one of the AO Tests then you are moved on the next leg of the journey. This step will determine whether one satisfies the Automatic UK Tests (“AUK Tests”). If one of the tests is met then the individual is UK resident.

If one has not met either of the above tests, then the journey continues on to a third and final leg.

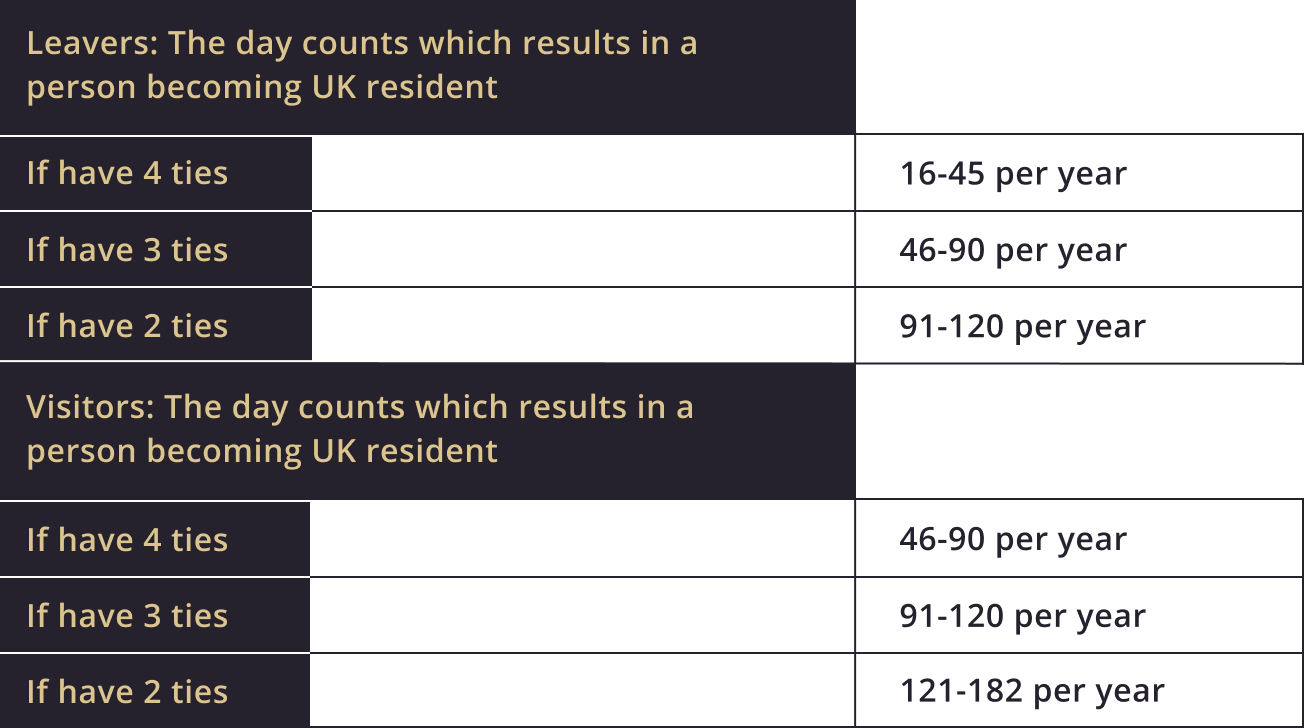

This involves considering whether one has ‘sufficient ties’ to the UK. The sufficient ties test is essentially a ‘day counting’ exercise. The rule of thumb is that the more ‘ties’ one has to the UK then the less days one can spend in the UK without becoming UK resident.

These thresholds differ depending on whether you are trying to ‘leave’ the UK or are a ‘visitor’.

The Automatic Overseas (AO) Tests

General

Technically, the legislation sets out five AO tests. However, from a practical perspective, there are really two tests here – one totting up days in the UK and the other identifying whether one works abroad on a full time basis.

Day-counting

As eluded to above, the day count test will differ depending on whether we are talking about someone leaving the UK (“Leaver”) or someone coming to the UK (“Visitor”):

- A Visitor is automatically non-UK resident if his days in the UK for the tax year are less than 46;

- A Leaver presents a slightly more complex position. The general rule is that he will be non-UK resident if his days in the UK number less than 16. However, in certain circumstances single day visits to the UK (i.e. no presence at midnight) can count towards the days.

Full time work abroad

In the pre SRT days, this was often the most certain method of becoming non-UK resident. It is good to see that this remains in a relatively unsettled form.

However, the test is slightly more complex than one might imagine – largely as a result of the second part of the test where one is determining whether the overseas work is full time or not.

First of all, the individual must meet a ‘threshold’ condition. This requires the following:

- The number of midnights spent by the Individual in the UK to be less than 91; and

- The number of days doing 3 hours of work or more in the UK to be less than 31.

Assuming the threshold test is met, we then need to go through a step by step calculation to see if the remainder of the test is satisfied.

In the first instance one must work out the taxpayer’s ‘net overseas hours’. Essentially, this is total overseas hours worked by the individual in the year, less any ‘UK work hours’. UK work hours are only deducted if the person worked more than three hours in the UK on a particular day (a UK work day).

A ‘reference period’ is then calculated by deducting the number of UK work days and days of holiday / sickness from 365 days. This reference period is then divided by seven to give a ‘number of weeks’.

The final step is then to divide the ‘net overseas hours’ by the ‘number of weeks’.

If the result of this rather laborious calculation results in 35 or more then the test is met.

The Automatic UK (“AUK”) Tests

General

As outlined, if one does not meet the AO Test then, and only then, do we move on to the AUK test. There are three limbs under which one might be automatically resident in the UK. You might be so resident under:

- A day-counting test;

- A home test; and

- Another full-time work test

Day counting

First of all, and quite simply, if a person spends 183 or more days in the UK then this is a point of no return. That person will always be considered as resident in the UK.

Home test

The second limb of the AUK test is the ‘home test’. For ‘home test’ it is perhaps better to think about it as the ‘only home test’.

It is mildly confusing at the nitty gritty level, however, one will meet the ‘home test’ in circumstances if you:

- have a home in UK and spend at least thirty days or part days in it; and

- do not have an overseas home (this second limb is a bit more nuanced than this but this gives you the gist).

In summary, one needs to have a UK home and not have an overseas home.

Full time work test

This test is almost exactly as the full time work test under the AO Test.

However, and rather intuitively, its purposes is to assess the work days in the UK rather than the days overseas. Therefore, we are interested in ‘net UK hours’ rather than ‘net overseas hours’.

If the final answer which pops out of the sausage machine is 35 or more then, this time, one is UK resident.

The key difference is that the reference period may be a 365 day period which is non-coterminous with the tax year.

If one does not come to an answer after reviewing the AUK tests then you move on to the ‘Sufficient ties’ test.

Sufficient ties test

This test involves applying a day count to a specific threshold.

However, that threshold is higher or lower depending on the number of ties one has with the UK. The more ties, the fewer days one may spend in the UK without being treated as resident for tax purposes.

It is first worth considering what constitutes a ‘tie’:

- Family tie: A person will have a family tie if a member of his family is UK resident. Broadly, family includes a spouse and minor children.

- Accommodation tie: A person will have an accommodation tie in the UK if he has property available for his use.

- Work tie: if the individual performs more than three hours work in the UK on 40 or more days in the tax year he will have a work tie.

- 90 day tie: if the individual spent 91 days or more midnights in the UK in one or both of the two prior years then he will have a 90 day tie.

There is, of course, much more depth and nuance to the definition of these ties. However, such detail is outside the scope of this article.

In addition, for ‘leavers’, there is a fifth potential tie which will be triggered where the personal has spent more midnights in the UK than in any other country.

The thresholds differ depending on whether one is a ‘leaver’ or an ‘arriver’. In summary, it is harder to escape from the UK, than it is for a visitor to become UK resident.

Conclusion

Under the old rules, in order to determine and individual’s residence status, we had an unsatisfactory ‘patchwork’ of case law plus HMRC’s published guidance in IR20. However, it was clear from seminal cases such as Gaines-Cooper that even HMRC’s guidance was beginning to creak at the seams.

Since the 2013/14 tax year, we have had cold hard legislation. It is not simple by any means as it is designed to catch a wide range of complex, modern practices. In our modern world, simplicity is probably too much to ask.

However, regardless of complexity, we do have some hard and fast rules. This will present some readily identifiable safe harbours in which a person can shelter if the fact patter permits.

Mosaic Chambers Group is a trading style of Mosaic Chambers FZ LLC

BUSINESS CENTER 05,

RAKEZ BUSINESS ZONE FZ

Email us

info@mosaicchambers.com

All Rights Reserved | Mosaic Chambers Group LLC | Privacy Policy