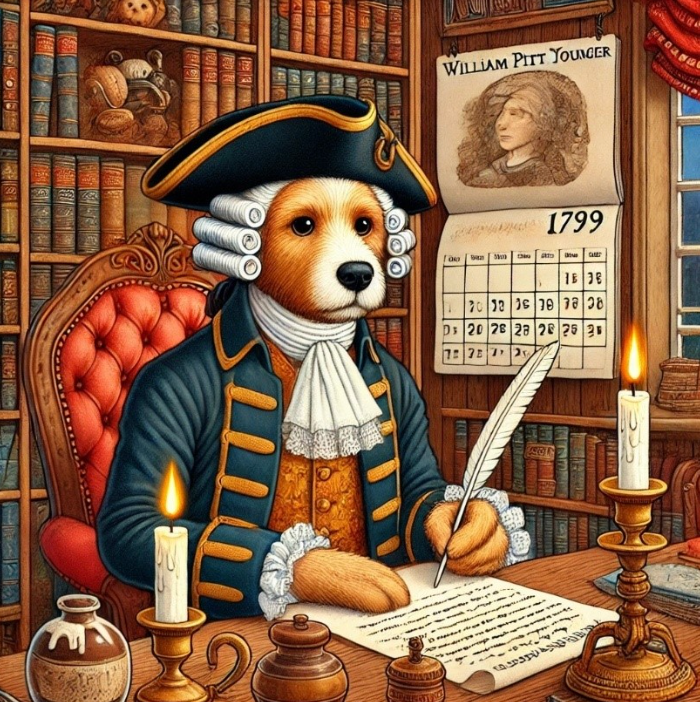

“Every dog has its day… or century or two”: The end of the remittance basis of taxation etc PART ONE

Andy Wood • February 18, 2025

This is the first in 3-part series on "The End of the Remittance Basis of Taxation"

Background – The British Bulldog v French Bulldog

PART 2

At the dying end of the 18th century, a little man with a big ego was throwing his weight around in Europe. His name was Napoleon. You might have heard of him.

At the same time, William Pitt the Younger, at an impossibly young age of 24, was the UK’s prime minister. He wasn’t given a particularly easy ride as, at the same time, King George III was losing his marbles.

In 1799, young Pitt introduced for the first time an income tax in order to pay for his fight with the angry little Frenchman. It was at this same time that he also introduced a remittance basis of taxation for overseas civil servants who, in today’s terminology, might be referred to as non-doms. The idea was to provide them with relief from these new taxes in relation to their overseas property.

Little did young Pitt know that he was creating a political football and a fiscal tightrope for centuries to come. Something that would only be cast aside some 226 years later.

So, it was a surprise when Jeremy Hunt the Beiger announced in Spring Budget 2024 the abolition of the remittance basis of taxation and, more generally, the removal of domicile as a main determining factor for UK taxation.

It was perhaps less of a surprise when Chancellor Rachel Reeves, with a slightly less impressive CV (even the made up one) when compared to Pitt, flourished the pen to sign the non-dom demise.

So, has the UK’s big tax dog finally had its day?

A woof guide to domicile.

So what is domicile and, by negative extension, non-domicile?

Although, unusually, domicile has had an important impact on a person’s tax position in the UK it is not a pure tax construct. It is a concept of general law.

It is therefore important to note that the proposed abolition of the non-dom tax changes are merely changes to the tax consequences of such a status. It does not change the position from a general law perspective. For example, they will apply to things like the law of succession and will even continue to be relevant for some double tax treaties.

Dicey, in his tome Conflicts of Laws, provides the authoritative definition of domicile of origin:

'every person receives at birth a domicile of origin…A legitimate child born during the lifetime of his father has a domicile of origin in the country in which his father was domiciled at the time of his birth'

In sum, one inherits a domicile of origin (“DO”) at birth. To use archaic terminology, where one is ‘legitimate’, then you inherit your DO from your father. Where your mother and father are not married, then a DO is inherited from one’s mother.

A DO is rather sticky and tenacious. There must be strong evidence that a domicile of choice (“DC”) has been acquired elsewhere for it to be overtaken. Indeed, one does not completely shed a DO. Instead, think of the DO as the foundation of a building. It will remain as it is until someone takes the trouble to build something on top of it. A DC might be built on this foundation.

Again, Dicey provides us with the commentary:

‘every independent person can acquire a domicile of choice by the combination of residence and intention of permanent and indefinite residence, but not otherwise’

As such, in order to build a DC, it is necessary to have:

- intention to reside permanently / indefinitely in a place; and

- physical residence in that place.

Where this is the case, and can be backed up by evidence, the edifice will remain strong.

However, where an element is missing then the walls will come tumbling down and you will be left with the foundations. In other words, your domicile of origin.

But this is a double edged sword.

What if little ‘ol me tried to assert I was domiciled in Spain? I have a domicile of origin in the UK (or should that be the People’s Republic of Yorkshire?) In order to develop a domicile of choice in Spain I would need to both be resident in Spain, but also show, and evidence, my intention to reside there indefinitely.

Of course, if I came back, or even just hopped across the border to France, then I no longer reside there and would no longer have a DC in Spain. My DO in the UK would revert. And that simply wouldn’t Labra-doo.

In part 2 of our series, we look at the pre-6 April 2025 rules, covering income tax, CGT, IHT, and trust regulations.

Find out what’s changing, why it matters, and how it could impact your financial planning.

By Andy Wood

•

April 1, 2025

For over two centuries, the UK’s non-domiciled tax regime and its remittance basis has been a cornerstone of tax planning for wealthy expats and international families. It was introduced, along with income tax, by Willian Pitt the Younger at the very end of the 18th century. It was part of the fiscal firepower necessary to battle Napoleon Bonaparte. And, like income tax, it had pretty much been a constant feature of the UK’s system ever since. But in March 2024, the then Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, rang the death knell for the remittance basis, with Labour’s Rachel Reeves – who would succeed Hunt a few months later - declaring she would have abolished it anyway. The end is therefore very much nigh for the UK’s non-dom tax regime. More specifically, the end is 6 April 2025. However, out with the old and in with the new’ goes the saying. As such, the ‘what comes next’ will reshape the tax landscape for non-doms, expats, and international investors with a UK footprint (or those considering creating one). What is Domicile (and Non-Domicile)? Domicile is not a straightforward concept like tax residence. The latter is largely about physical presence (or otherwise) in a particular. Instead, as well as physical presence, it also requires an understanding of your future intentions. Is a place somewhere that you intend to live permanently or indefinitely. There are two main types of domicile that I will discuss here: • Domicile of origin: This is inherited at birth, usually from your father (if you think that is misogynistic then I don’t make the rules, OK?). You do not lose your domicile of origin. However, think of it as the foundations of a building. You can a domicile of choice on top it. • Domicile of choice: You build a new domicile of choice by achieving two things. Firstly, by physically residing in place and, secondly, by forming the intention to stay in that same place permanently or indefinitely. Both must be present.

By Andy Wood

•

March 26, 2025

So you’ve left the UK for pastures new. The sun is shining. You're making more money. You’re enjoying a great quality of life in a new country. In fact, you’re totally de-mob happy. Even better, as a non-UK resident, UK taxes are a dim and distant unpleasant memory, right. Right? Wrong. I don’t necessarily see my role in life as chief balloon popper. However, there are some Uk tax things you should bear in mind before declaring yourself a tax exile. Am I really non-UK Resident (“NR”)? Up until 2013, the UK didn’t really have a statutory definition of residence for tax purposes. Yes, that’s as crazy as it sounds. Fortunately, the Statutory Residence Test (“SRT”) was introduced from 2013. The idea is that it provides a degree of objectivity through a series of tests. Although a statutory test, other than in straightforward cases, it can still remain complex.

Mosaic Chambers Group is a trading style of Mosaic Chambers FZ LLC

BUSINESS CENTER 05,

RAKEZ BUSINESS ZONE FZ

Email us

info@mosaicchambers.com

© 2025

All Rights Reserved | Mosaic Chambers Group LLC | Privacy Policy